Error correcting codes, duality, and the devil's chessboard

I was browsing twitter early one morning, and I came across this tweet.

It took a while for me to fully understand what the question was asking. So to clarify:

An 8x8 chessboard starts out with 64 coins laid on it in a random permutation. A person points to a position on the chessboard, say g4 in chess notation (row 4 column 7). You must tell your friend that the pointed to position was g4. The only communication you can do is flipping a single coin on the board. The wording is unclear in if we may or must flip a coin, but let’s just say we must flip a coin.

Browsing through the comments, I saw that one of the comments said something something “error correcting codes”. This gave me an idea. The whole point of error correcting codes is to be as tolerant to adversaries as possible. In other words, we need many different bit strings to encode to the same symbol, so flipping certain bits still keep you at the same symbol. But here, we want the opposite. We want a single flip of the chessboard to be able to bring us to every other symbol.

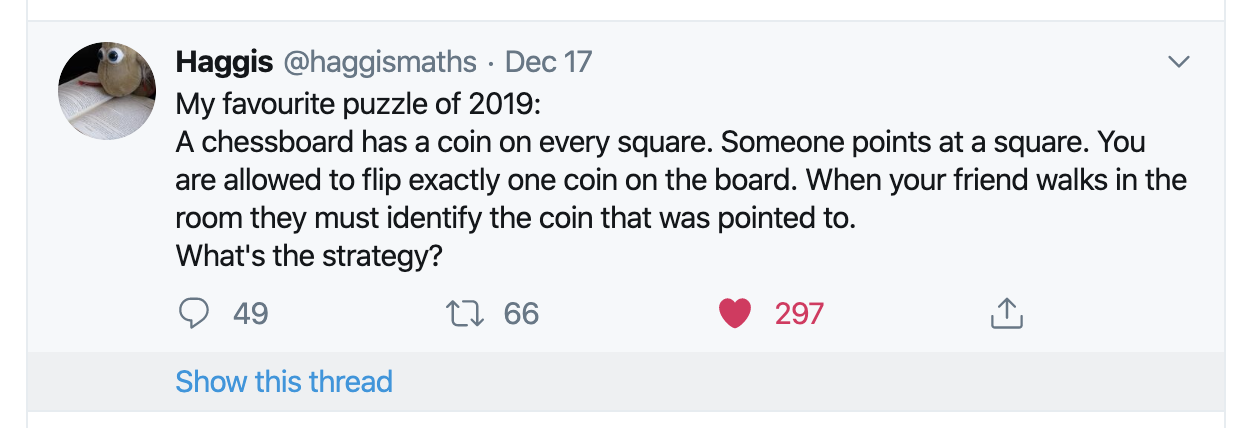

What is the most “disruptive” that a single bit can be? Let’s label the chessboard using length 6 bitstrings:

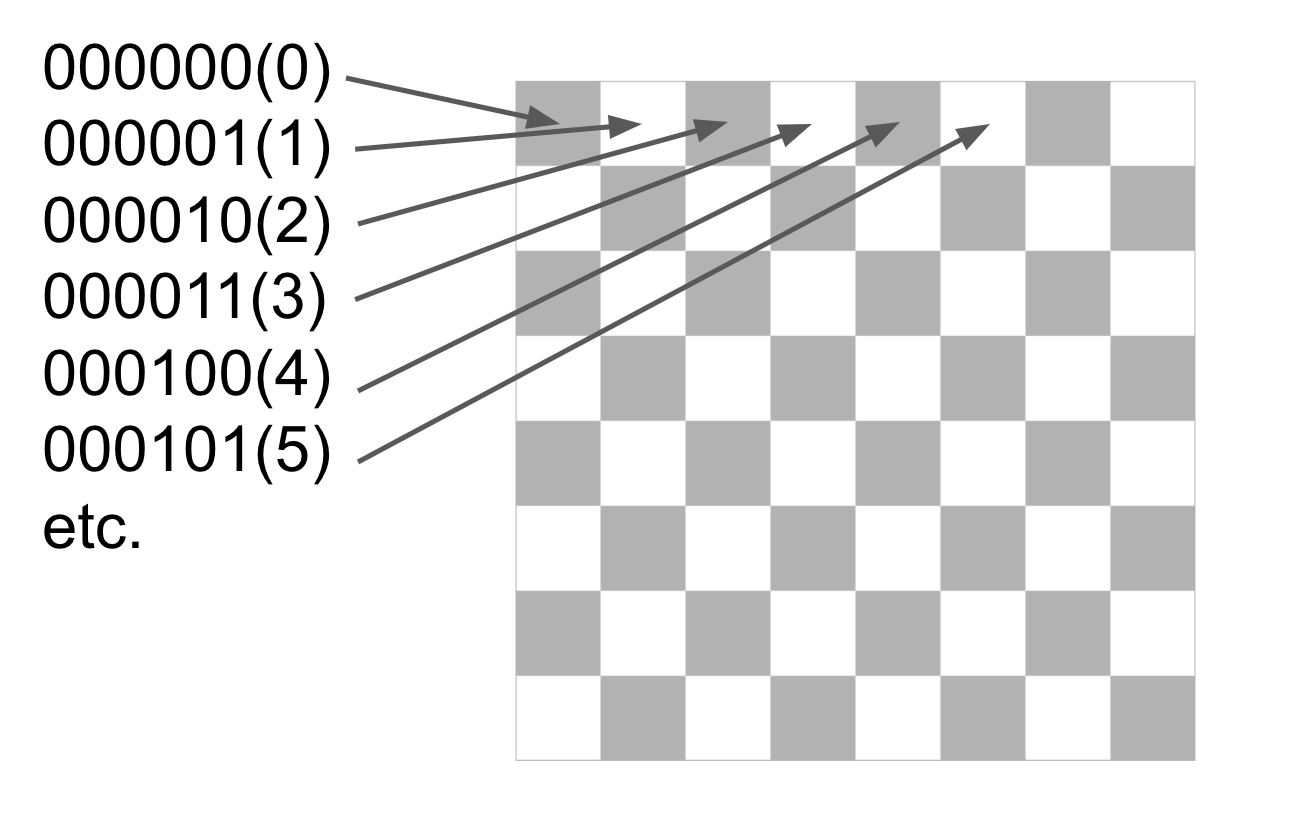

We want the flip of any single coin to be as “selectively disruptive” as possible. What this means is, if the starting configuration of the board tells some information (the secret position), then the flip of some coin must be able to take us to any other encoded position. Here we have a random starting position of the chessboard.

Clearly, we haven’t defined what position this chessboard encodes, but what we do know is that the flip of a particular coin on this chessboard will allow us to represent the encoding of any position. This motivates us to try the following:

Encoding scheme: Given a chessboard configuration, to find the position that it encodes, recover the length 6 bitstring by finding “parities”. The “parity” of the \(i\)th position is defined as 0 if there are an even number of heads on all squares with a label “1” in the \(i\)th position.

This can be understood much clearer via an example. We want to recover abcdef, which is going to be a bitstring that represents the location of the secret position. To recover “a”, look at all 32 squares whose location starts with “1”. If there are an even number of these, \(a=0\), else \(a=1\). To recover “b”, do the same thing, but look at all 32 squares whose location’s 2nd bit starts with 1.

Fact: Flipping the coin on position 110110 will flip the first, second, fourth, and fifth bits of our final encoding. In general, flipping the coin at position abcdef will flip all bits in the final location encoding, only if that bit at the coin position was “1”.

And finally, if no bit needs to be flipped, then just flip the coin at position 000000, as this will not change the encoding.

Credit for this solution goes to G.J. Woeginger from this thread, which seems to be a mailing list on computing theory. Apparently this is a standard problem in coding theory.

As a final remark, there surely can be a lot to explored on the relationship between this scheme, and it’s relationship to error correcting codes. There must be some duality, but I think I will leave this blog post here.