Coherence, Gambling, and Philosophy

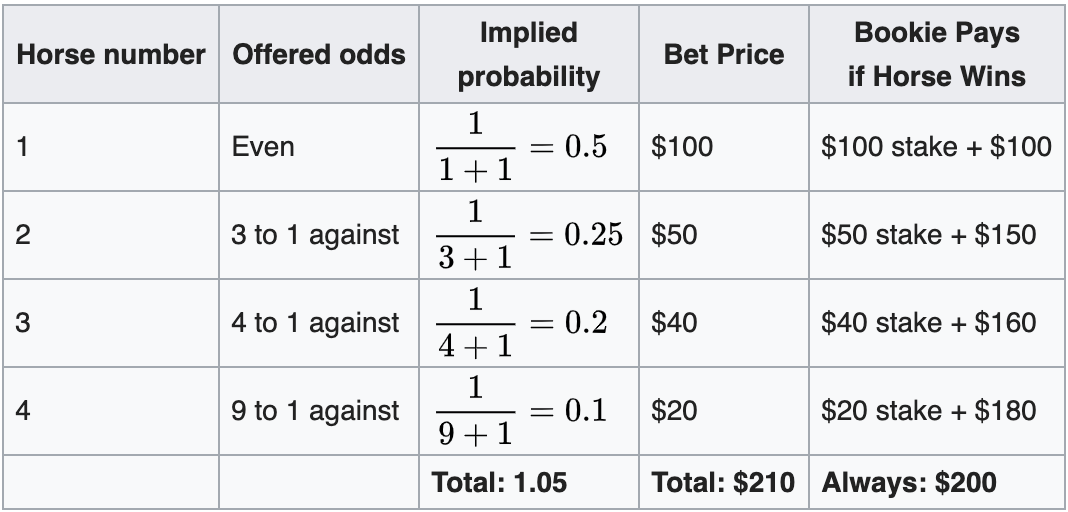

Suppose you are at a horse race, and a bookmaker comes to you with the following offer:

A fact about gambling is implied odds. If you risk 5 dollars to win 10 dollars based on the outcome of an event, then you are implicitly saying that you believe the event will occur at least 50% of the time. If you risk 5 dollars to win 6 dollars, then you must believe that this event will occur at least with probability $\frac{5}{6} \approx 0.83$. That is assuming that we are rational.

In the above table, there are 4 mutually exclusive events, each of which being 1 of the 4 horses winning a horse race. However, because the bookmaker has layed odds that don’t add up to 1, and is significantly greater than 1, if a better were to make each one of the 4 bets, then the bookmaker is guaranteed to make money.

Now according to the Wikipedia article on Coherence and Dutch Books, which is the jargon for scenarios like this where the bookmaker is guaranteed money, there is supposed to be a deep philosophical implication here. I may be completely misinterpreting it but here goes nothing:

Bayesian viewpoint: Random events have distributions, and we can validly model these distributions using our beliefs. i.e.: I believe that horse 1 will win 25% of the time, because horse 1 has won once in his last four races.

Frequentist viewpoint: No. Random events do have distributions, but you can only say for sure what that distribution is in the limit of your number of trials. i.e.: I know this coin has probability of landing heads with probability $\frac{1}{2}$ because my Python script flipped the coin 1,000,000 times, and 499,987 of them were heads.

The problem is horse races are not coin flips. You can’t reproduce them.

So the Dutch book as shown above tells us that if our odds that we lay are coherent, i.e. follows the rules of probability, like having all mutually exclusive events sum to 1, then it is impossible to construct such a Dutch book.